Australia So Much to See

During the 1890s typhoid fever in the goldfields reached epidemic proportions. An infectious food and water borne disease, typhoid

was linked to poor sanitation, often combined with overcrowding - which was very common in Coolgardie.

Crowded tent towns,

unsanitary conditions, and a very limited water supply, combined with only basic health amenities, provided ideal conditions for the

spread of the disease. The disease's greatest impact was during the long hot summer months.

In the early years if the epidemic,

up to twenty of mostly healthy young men died. Nearly 2,000 people in Western Australia were officially recorded as dying of

the disease, though the actual number was far greater. Most deaths occurred on the goldfields, where and estimated ten times

more people suffered from the disease. It was by far the largest episode of epidemic typhoid in Australia’s history. By

the 1910s it has started to ease a little.

The risk of death from typhoid was compounded by the lack of hospitals and

nurses on the goldfields. When the extend of the emergency was recognised, the government provided tents for emergency hospitals.

Coolgardie Children’s Hospital – a WA first. In March 1897, the construction of a brick and stone sixteen bed hospital for children

commenced, with funds raised locally, on land granted by the Government at the corner of Hunt and Woodward Streets. The hospital

was at the time unable to accommodate children, who were expected to be nursed at home. This was the first children’s hospital in

Western Australia.

Subsequently an extension was built at the main hospital to accommodate children, and in 1904 the building

became an infectious diseases hospital. Ruins of the foundations are all that now remains.

Varischetti recovered and returned to work underground, however he succumbed to the then common miner’s lung disease, fibrosis, thirteen

years later.

References

West Australian International Mining and Industrial Exhibition 1898 Trove

West Australian International Mining and Industrial Exhibition 1898 InHerit

Coolgardie Children’s Hospital

Signage

and information sheets on site.

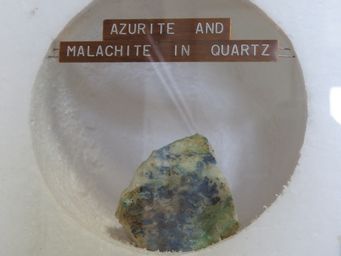

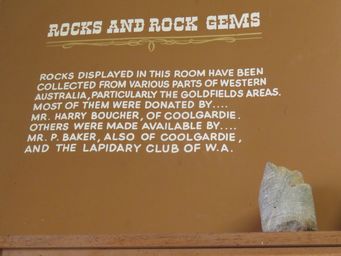

Other upstairs collections include the Rock and Gem display, which features rocks from all over Western Australia, but principally

from the goldfields. Each stone is labelled.

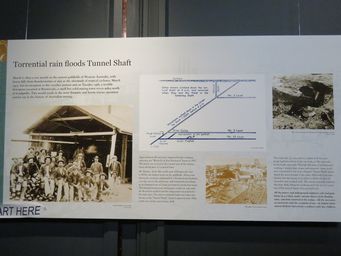

With the mine flooding miners and underground employees

somehow managed to return to the surface. All the men were accounted for with the exception of one, Modesto Varischetti, a widower

with five children.

COMING SOON

COMING SOON

COMING SOON

Varischetti, on the number 10 level, knew he was trapped. Although below about 50 feet of water, he was in an air pocket and able

to breathe. His workmates, assuming him dead, were amazed to hear his taps from below the waterline.

A chance remark by the mine

manager's son to use a diver triggered a dramatic rescue which involved two divers, Jack Curtis and Tom Hearne, along with their assistants

and diving gear. Two Kalgoorlie miners, Frank Hughes and Fox, also offered their diving and mining expertise.

The nearest

air hose long enough to reach Varischetti was in Fremantle, 560 kilometres away. The West Australian government ordered a special

train, the Rescue Special, which cut nearly two hours off the twelve hour run to Coolgardie, setting a world record for the distance.

At Coolgardie, fast horses rushed the equipment to Bonnievale.

Hughes made his first exploratory dive on the fourth day of Varischetti's ordeal. He and Hearn made three separate descents

on day five, and on day six, when they first reached the trapped man, giving him an electric lamp, food, candles and other necessities. Varischetti was visited each day by the divers while enough water was pumped to allow access on foot.

By day nine, there

were serious concerns about his health and chances of survival, so the divers tied a rope around Varischetti's waist and started the

difficult walk back up through the deep water and sludge, where at times he was almost fully submerged. He staggered to the surface

on March 28, 1907 after 206 hours underground.